The Military History of the Declaration of Independence Symposium

March 1, 2025 at the UTK Baker Center

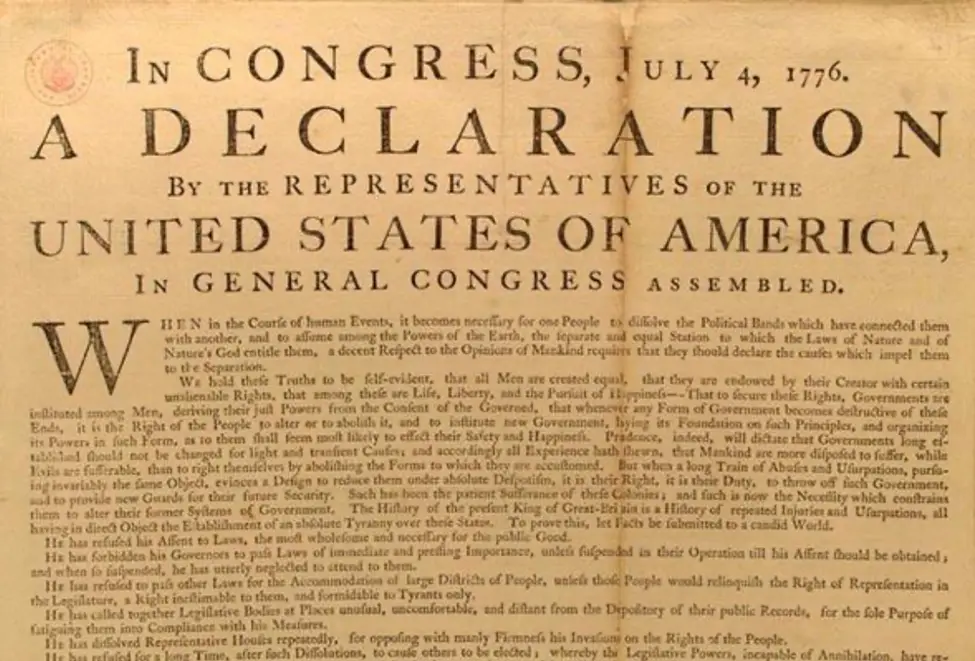

As the 250th anniversary of the signing of the Declaration of Independence approaches, it is important to remember that this foundational document was written during a war. The Declaration was, in large part, a Congressional war measure. It was meant to convince potential allies overseas and fence-sitters at home that the British government had devolved into a tyranny.

We will hold a symposium on the military history of the Declaration of Independence at the UTK Baker Center on March 1, 2025, 10am to 3pm. Nine scholars from universities around the country will come to Knoxville to present their original research. Dr. Ricardo A. Herrera will give a keynote address. Dr. Herrera is a Visiting Professor in the Department of National Security and Strategy at the US Army War College. His book Feeding Washington’s Army (2022) was a finalist for the American Battlefield Trust Book Prize for History.

The symposium is generously sponsored by the Center for the Study of Tennesseans and War, the Department of History, the Baker School of Public Policy and Public Affairs, the East Tennessee History Center, and the Society for Military History.

Seating is limited. Please register here.

PROGRAM

9:00-9:30am

- Coffee and Refreshments

9:30-10:00am

- Opening Remarks by Dr. Chris Magra, Professor of History, Director of the Center for the Study of Tennesseans and War

10:00-10:30am

- Dr. Michael Lynch, Lincoln Memorial University, “Innocents and Indian Warfare in the Declaration’s Rhetoric”

- Abstract: The final charge in the Declaration of Independence’s list of royal abuses accuses George III of unleashing “the merciless Indian Savages, whose known rule of warfare, is an undistinguished destruction of all ages, sexes and conditions.” This passage suggests the importance of anti-Indian sentiment to the Revolutionary cause. Both Peter Silver and Robert Parkinson have demonstrated that animus toward Indians was a critical component of identity formation and political/military mobilization for eighteenth-century Euroamericans. But Jefferson’s words indicate that what most horrified Revolutionary Americans about the prospect of Indian war was not only the identity of their adversaries, but the composition of the victims. This presentation places the Declaration’s reference to “merciless Indian savages” in the context of eighteenth-century thinking about gender, age, and warfare. Early Americans considered violence against women, children, and the elderly to be heinous and “unmanly.” They believed such violence was a distinguishing feature of Native American war, and accounts of Indian attacks consistently highlighted the plight of these innocents. Convinced that imperial authorities directed the attacks, Revolutionaries invoked these vulnerable victims to denounce the British war effort as barbarous and illegitimate—even though colonists had long employed “undistinguished destruction” when campaigning in Indian country.

10:30-11:00am

- Dr. Stuart Marshall, Sewanee–The University of the South, “Combating Revolutionary State Formation in Cherokee Country”

- Abstract: “Canaly” was the reported dying word of a Cherokee man in 1776 as he fell at the hands of a Patriot. This story, retold by various historians, has been continuously misinterpreted; the dying word lost in translation. Actually oginali in the Tsalagi language (meaning “my friend”), the victim was pleading for mercy, asking for a ceasefire that would never come. The “merciless Indian Savages” of the Declaration of Independence was an artful turn of phrase—and common trope in settler colonialism—which made invasion and plunder appear as self-defense; bloody aggression as pacification. This infamous phrase served as a rallying cry for the Whig Indian War of 1776. Intended to mobilize backcountry militias, the phrase emboldened rogue colonies on Cherokee land to claim new legitimacy in rejection of British tyranny. This paper investigates the fight for revolutionary state formation in Tennessee by tracing its origins in the exodus of North Carolina Regulators and creation of the Watauga Association and Henderson Purchase. Despite Cherokee restraint and resistance, Patriots began their Revolution by laying waste to Cherokee country. Featured evidence includes court records and petitions, pension records, the Draper Manuscripts, intercepted Cherokee documents, and the Treaty of Long Island of Holston.

11:00-11:30am

- Dr. Ross Nedervelt, Florida International University, “The Declaration of Independence, Islanders’ Sympathies, and the Emergence of the Revolutionary Atlantic Border-sea”

- Abstract: Continental Congress delegates employed specific grievances in the Declaration of Independence to sway neighboring colonies to join their revolt against Britain. The Royal Navy’s impressment activities against the North American mainland colonies’ sailors constituted a critical grievance that appealed to sympathetic Bermudian merchants and mariners. American patriot officials, specifically Benjamin Franklin and Silas Deane, argued that by bringing Bermuda into the union against Britain, an independent United States could extend its authority further into the Atlantic and secure its maritime frontier and commerce from future attacks. Papers from the delegates, George Washington, and Bermuda-born St. George Tucker demonstrate the Patriots’ sustained efforts to convince Bermudians to declare independence and join the revolutionary effort. Despite these efforts, American patriots’ failure to convince Bermuda to join the revolution proved unsuccessful, and the island emerged as a critical maritime border region that threatened the United States’ sovereignty between 1783 and 1816. At Bermuda, British military forces pivoted to bolster their position in the western Atlantic. Consequently, they forced the United States to fight a second war for independence against increased British impressment and naval attacks, which challenged Americans’ citizenship and destroyed the nascent nation’s capital during the War of 1812.

11:30-noon

- Dr. Robert Parkinson, Binghamton University, “Executioners of Friends and Brethren?: Exploring the Declaration’s Naval History”

- Abstract: The second-to-last grievance in the Declaration cries that the King had “constrained our fellow Citizens taken Captive on the high seas to bear arms against their country, to become the executioners of their friends and Brethren, or to fall themselves by their Hands.” This paper will explore the evidence behind that rather explosive accusation, and how and why this particular grievance found its way into the Declaration.

Noon-1:00pm

- Catered Lunch and Keynote Address

- Dr. Ricardo A. Herrera, US Army War College, “Scouting the Field: Surveying the Military History of the American War for Independence”

- Abstract: General George Washington had a few things to say about “The history of the war,” and little of it was positive. Writing on 4 October 1780 to James Duane, a New York delegate to the Second Continental Congress, Washington opined that “The history of the war is a history of false hopes and temporary expedients—Would to God they were to end here!” The commander-in-chief gave freer rein to his frustration the next day in a letter to Brig. Gen. John Cadwalader of the Philadelphia Militia. Noting the army’s perpetually faltering, staggering, stumbling supply system, Washington vented that “We have no Magazines, nor money to form them. And in a little time we shall have no men, if we had money to pay them. We have lived upon expedients till we can live no longer—In a word the history of the War is a history of false hopes and temporary devices, instead of system & œconomy.” His Excellency was not happy, but for students of the American War for Independence, this is not the case. Indeed, as the United States approaches the semiquincentennial of the war’s outbreak on 19 April 1775 and of the Declaration of Independence, the state of the Revolution’s military history is full of real hopes, accomplishments, and even “system & œconomy.” Over the past several years, historians have put forth an impressive amount of scholarship examining the war. To say that it is expansive would be an understatement, yet opportunities for further research abound. This moment presents an opportunity to scout the field of the American Revolution’s military history, to assess its state, and to consider possible paths for historians.

1:00-1:30pm

- Dr. Mark Schmeller, Syracuse University, “To Supply the Defect of Principle: Oaths in the Declaration and War of Independence”

- Abstract: This paper begins with the last sentence of the Declaration of Independence: “And for the support of this Declaration, with a firm reliance on the protection of divine Providence, we mutually pledge to each other our Lives, our Fortunes and our sacred Honor.” It is rarely noted that the Declaration ends with an oath: a solemn promise invoking a divine witness to one’s future action. Understanding the Declaration as a wartime document helps us to better understand the meaning and implications of that sentence. Discerning and securing the loyalty of civilians and soldiers is a perennial wartime problem, and legislators and military officers often resort to oaths to achieve those ends. My paper will survey the variety of oath-making practices during the war, from the Continental Association of 1774, to civilian oaths of fidelity and support administered in many states, to the 1778 oaths required of Continental Army officers. George Washington’s view on the instrumentality of oaths will receive particular attention. Oaths were in his estimation “the only substitute that can be adopted to supply the defect of principle.”

1:30-2:00pm

- Travis C. Perusich, University of Arkansas, “All Men Are Created Equal: How the Declaration of Independence Became a Tool for Black Freedom”

- Abstract: The most important passage of the Declaration of Independence is not in the document. Jefferson’s original draft included a vigorous condemnation of slavery. “He has waged cruel war against human nature itself, violating its most sacred rights of life and liberty in the persons of a distant people who never offended him, captivating & carrying them into slavery in another hemisphere or to incur miserable death in their transportation thither.” But this passage was cut in the name of ensuring the slave South would adopt the document. Despite this omission, thousands of African American Patriots fought on and off the field to promote the ideals of liberty invoked by the Declaration. Black Patriots saw the Declaration of Independence as a tool by which to secure black freedom. During the war, black soldiers used Declaration ideology to secure freedom from slavery, while black poets used the ideas espoused by the Declaration to illustrate the hypocrisy of fighting a war for black freedom while maintaining black slavery. Following the war, black abolitionists would use the Declaration as a means of attacking institutional slavery as a whole, while black veterans used it to personally advocate for their own rights as veterans.

2:00-2:30pm

- Dr. Alex Beckstrand, University of Connecticut, “Civil-Military Relations and the Declaration of Independence: Preliminary Principles and Lasting Legacies”

- Abstract: Beyond being a war measure, the Declaration of Independence provides insight into sentiments regarding the unique conduct of American civil-military relations – that is, the proper relationship between the military and society. The document revealed important principles harbored by the drafters and signers. A common belief in the general necessity of military force was noted in the fearful blaming of the King for leaving the colonies “exposed to all the dangers of invasion from without, and convulsions within.” A wariness of the militarization of society was mentioned in the grievances concerning quartering of troops and the maintenance of a large peacetime army in the colonies. The signers made known their preference for civilian control over the military by condemning the King, who “affected to render the Military independent of and superior to the Civil power.” And the Declaration ends proclaiming the rights of Congress and the States to make war and peace. These and other ideas outlined in the document were crucial for the how the United States conducted the War of Independence, how the young nation established its original civil-military principles, and how those legacies of civil-military relations continue to modern times.

2:30-3:00pm

- Dr. Michael P. Gabriel, Kutztown University, “‘For abolishing the free system of English laws in a neighboring province’: The 1775-1776 Canadian Campaign and the Declaration of Independence”

- Abstract: The 1775-1776 Canadian Campaign played a role in the writing of the Declaration of Independence. The Declaration includes the 1774 Quebec Act among the list of “pretended legislation” that George III “assented to.” Americans considered the act as the fifth “Intolerable Act,” as it recognized French law in Quebec, created an appointed government with no elected assembly, and expanded the provinces borders to the lands north of the Ohio River. In Fall 1775 two separate American forces invaded Canada in an attempt to encourage its inhabitants to send delegates to the Continental Congress and embrace the colonists’ cause. The Americans also hoped to deprive the British from using Canada as a staging area to attack the frontier. By the time Jefferson wrote the Declaration in June 1776, American forces had suffered defeat and were retreating from the province. A British army composed of “foreign mercenaries” – the first to land in America, months before those who arrived at Staten Island – and “merciless Indian savages” was gathering at St. Jeans on the Richelieu River, preparing to invade New York and New England. Additionally Thomas Paine’s appeal for independence, A dialogue between the ghost of General Montgomery just arrived from the Elysian fields and an American delegate: in a wood near Philadelphia (1776), featured a martyr of the Canadian invasion, General Richard Montgomery.

3:00-3:30pm

- Closing Remarks by Dr. Chris Magra, Professor of History, Director of the Center for the Study of Tennesseans and War

PRESENTER BIOS

Dr. Michael Lynch is Director of the Abraham Lincoln Library and Museum at Lincoln Memorial University. His research focuses on the American Revolution in the backcountry South and Appalachian frontier.

Dr. Stuart Marshall is a Visiting Assistant Professor of History at Sewanee–The University of the South. Marshall’s published work on revolutionary America includes a reinterpretation of North Carolina’s Regulator movement and inquiry of disputed boundaries in the southern backcountry. He is working on a book based on his dissertation, “The Age of Junaluska: Eastern Cherokee Sovereignty in the Long Civil War Era,” which he completed in 2023 at the University of North Carolina at Greensboro. Marshall is also active in the Tennessee Trail of Tears Association and as a team member of ECHT (Eastern Cherokee Histories in Translation).

Dr. Ross Nedervelt is an adjunct professor of history at Florida International University in Miami, Florida, where he received his Ph.D. in 2019. He specializes in border regions, identity, and security in the British Atlantic world during the long eighteenth century. His in-progress monograph, presently titled Revolutionary Border-sea: Security, Imperial Reconstitution, and the British Atlantic Islands, 1763-1825, examines the transformative impact of the American Revolution on Bermuda and the Bahamas, and their strategic importance for both British and American security in the Age of the American Revolution. Previously, published works include “Caught between Realities: The American Revolution, the Continental Congress, and Political Turmoil in the Bahama Islands,” in the Journal of Imperial and Commonwealth History, as well as “Securing the Borderlands/seas in the American Revolution: The Spanish-American Association and Regional Security against the British Empire” in Spain and the American Revolution: New Approaches and Perspectives (Routledge; reprinted by the University of Virginia Press). Dr. Nedervelt teaches U.S. and Caribbean history with a focus on seventeenth- and eighteenth-century British America, the comparative colonial Caribbean, U.S.-Caribbean relations, and revolutionary and resistance movements.

Dr. Robert Parkinson is Professor of History at Binghamton University, and the author of Thirteen Clocks: How Race United the Colonies and Made the Declaration of Independence. His latest book, Heart of American Darkness: Bewilderment and Horror on the Early Frontier, was published in 2024.

Dr. Ricardo A. Herrera is Visiting Professor, Department of National Security and Strategy, US Army War College, and an award-winning historian. He is the author of Feeding Washington’s Army: Surviving the Valley Forge Winter of 1778 (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2022), For Liberty and the Republic: The American Citizen as Soldier, 1775-1861 (New York: New York University Press, 2015), and of several articles and chapters on US military history. Herrera is now completing the tentatively titled book, A Most Uncommon Soldier: The Life, Letters, and Journal of Edward Ashley Bowen Phelps, 1814-1893, an edited collection, to be published by the University Press of Kansas. His next project will examine the 1778 and 1779 campaigns for Savannah.

Before joining the Army War College, Rick Herrera was Professor of Military History at the School of Advanced Military Studies, US Army Command and General Staff College and Team Chief, Staff Rides, Combat Studies Institute. In November 2020, Herrera was elected a Fellow of the Royal Historical Society. A graduate of Marquette University (PhD, 1998) and the University of California, Los Angeles (BA, 1984), Herrera has taught at Mount Union College and Texas Lutheran University. Before becoming a historian, Herrera spent five years in sales and served three years as an armor and cavalry officer in the US Army. In October 2024, the State Society of the Cincinnati of Pennsylvania inducted him as an honorary member.

Dr. Mark Schmeller is Associate Professor of History at the Maxwell School of Citizenship and Public Affairs at Syracuse University. He is the author of Invisible Sovereign: Imagining Public Opinion from the Revolution to Reconstruction (Johns Hopkins University Press, 2016). Schmeller has received fellowships from the Mellon Foundation, the Library Company of Philadelphia, and the Charles Warren Center for Studies in American History at Harvard University. He is currently at work on a history of the 1826 kidnapping and murder of William Morgan, a Freemason who had threatened to reveal the secrets of the fraternal order.

Travis Perusich is a PhD Candidate at the University of Arkansas. He is writing a dissertation on the role of African American soldiers during and after the American Revolution.

Dr. Alex Beckstrand is a historian and an adjunct professor at the University of Connecticut and Central Connecticut State University. He is an officer in the Marine Corps Reserves and works in the aerospace industry. His work has appeared in the Journal of Military History, Georgetown University, the Washington Post, Strategy Bridge, and the National Interest.

Dr. Michael P. Gabriel is Chair of the Department of History at Kutztown University of Pennsylvania. He earned his master’s and doctorate at Saint Bonaventure and Penn State Universities, respectively. He is the author or editor of five books, including Major General Richard Montgomery: The Making of an American Hero (2nd edition forthcoming); Quebec During the American Invasion, 1775-1776: The Journal of François Baby, Gabriel Taschereau, and Jenkin Williams; and The Canadian Campaign, 1775-1776 (forthcoming).

Dr. Chris Magra is a Professor of Early American history at the University of Tennessee. He is also the Director of the Center for the Study of Tennesseans and War. His first two books were bottom-up histories of the American Revolution that explained why maritime laborers resisted British authority. He has been a research fellow at the David Library of the American Revolution, the Massachusetts Historical Society, the Peabody Essex Museum, and the University of Tennessee’s Humanities Center.